NYISO: The current landscape of BESS permitting

Permitting occurs when an Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ) determines that a project is safe to build, safe to operate, and poses no undue risk to the surrounding environment. It is a critical stage in development for any battery energy storage project.

In New York, permitting has become a structural constraint on the construction of grid-scale storage. Permitting can materially delay project timelines, and in some jurisdictions, moratoria or outright bans have halted projects in early development.

Batteries in New York face other obstacles, such as merchant revenue risk and interconnection wait times. However, while the ISC mechanism and interconnection reform begin to address those challenges, a clear pathway to de-risk permitting remains elusive.

Key Takeaways

- Permitting processes vary widely across the state, with timelines ranging from several weeks to months, and 108 AHJs have enacted moratoria or bans on BESS development.

- Moratoria and bans can lead to costly project withdrawals exceeding $2 million due to non-refundable land and interconnection expenses.

- New York City differs from the rest of the state. It has three structured permitting processes involving the Fire Department, the Department of Buildings, and the local utility, Consolidated Edison.

- NYSERDA’s permitting guidebook and efforts to expand permitting at the state-level may help reduce risk outside of New York City.

New York State does not a have a unified permitting process for battery energy storage systems

In New York State, review timelines and requirements can vary widely for identical projects in different AHJs. This variation reflects uneven local ability to address concerns about proposed BESS projects.

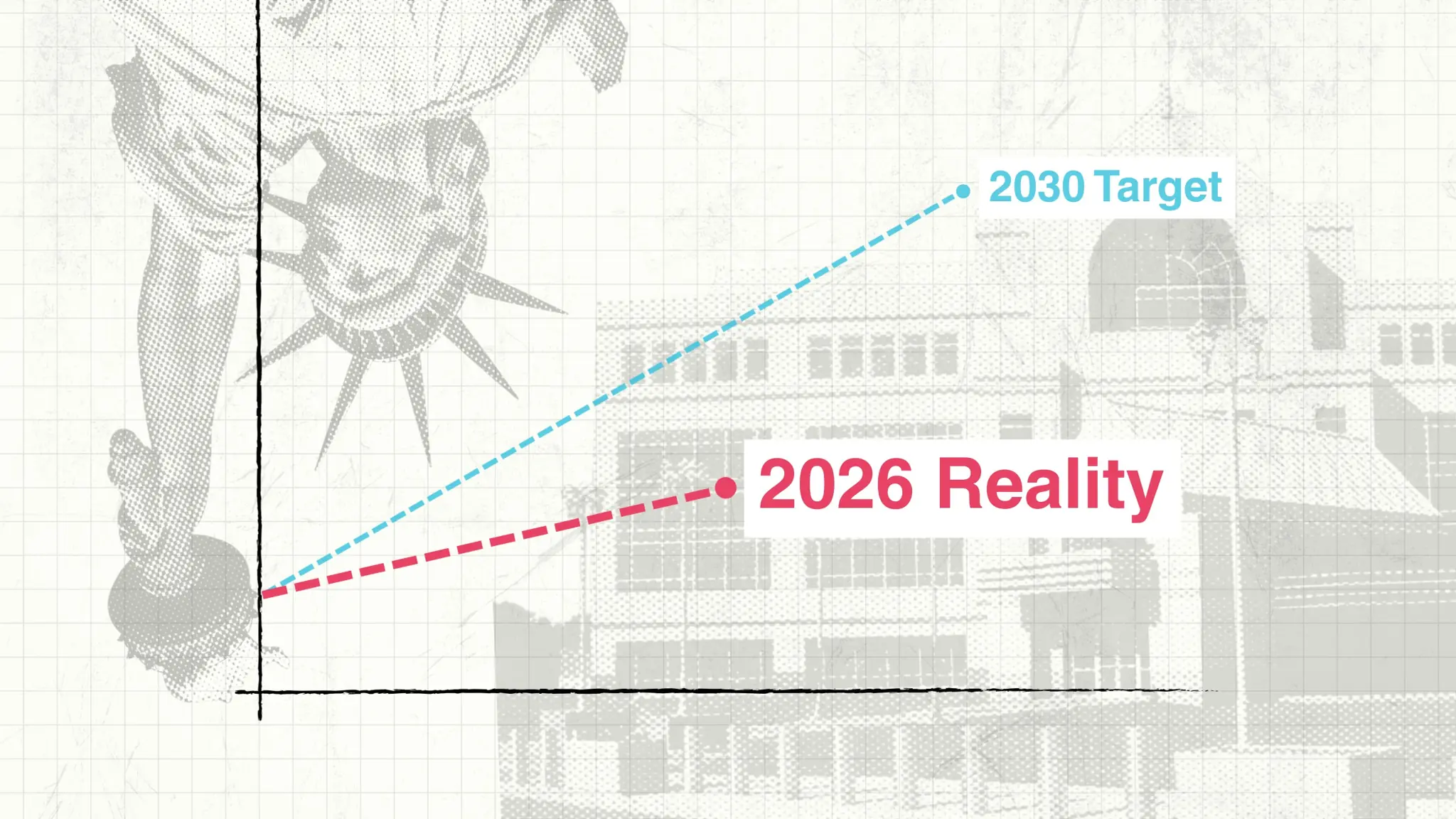

In response, many AHJs have imposed moratoria to temporarily pause battery development while they address policy, safety, and community concerns. As of September 2024, 1 GW of battery energy storage in the queue was under moratoria.

Some jurisdictions have gone further by introducing Primary Use Bans (PUBs). These permanent zoning restrictions prohibit standalone BESS and allow batteries only as an accessory to other permitted activity. PUBs lock long-term constraints into local codes instead of addressing impacts through technical review. Bans tie eligibility to land-use classification rather than project design or operational metrics.

According to American Clean Power, 108 AHJs had either moratoria or PUBs on grid-scale BESS as of November 23, 2025. These ordinances cover a combined area of 4,500 mi² (or 8% of New York State.) Of these 108 AHJs, 50 towns and cities had both moratoria and PUBs in place, as bans are often enacted while moratoria remain active.

The outcome is an uneven regulatory landscape across the state, where BESS developers face significant obstacles, some of which may lead to costly project withdrawals.

Permitting complications present significant financial risk to BESS developers in New York

Developers often pursue permitting in parallel with interconnection studies to accelerate timelines to commercial operation.

While this approach historically shortened development timelines, it introduces new risks under the reformed interconnection process.

Because the new interconnection process requires deposits before and after each phase, projects may commit significant capital before an AHJs ordinance freezes development. The requirement to demonstrate land ownership further increases upfront costs for battery projects.

The charts below estimate the non-refundable expenditures of four hypothetical battery projects in New York’s interconnection queue. They assume that each project pays land lease costs on a yearly basis and incurs no network upgrade costs for interconnection, which could potentially understate actual expenditures.

Depending on the point of withdrawal, the smallest hypothetical project would forgo between $200,000 and $800,000, while the largest would forgo between $500,000 and $2.2 million.

These differences largely reflect how land costs and interconnection readiness deposits scale with battery size.

Although these unrecoverable costs present a major risk to developers, there is one zone with no moratoria or bans - New York City.

New York City has a consistent, but stringent, permitting regime that minimizes ordinance risks

In New York City, the permitting process is highly standardized. It requires input from the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), Consolidated Edison (ConEd), and the Department of Buildings (DOB). Each agency reviews the project and issues permits via processes based on battery size.

Almost all grid-scale batteries are considered “large” and require 10 permits and approvals. Developers typically pursue these from all three organizations in parallel, and the process can take months to years to complete.

While grid-scale batteries face minimal moratoria or ordinance risk due to a consistent permitting regime, the multi-agency approval process leads to longer development timelines.

This level of stringency reflects New York City’s elevated fire safety concerns as the densest city in the United States. Additional guidance addresses setback requirements, noise limits, stormwater management, and other potential BESS impacts.

Efforts are underway to standardize permitting beyond New York City

Fragmented permitting processes and the risk of local ordinances continue to hinder the development process. Clear, consistent standards can both protect public safety and enable orderly battery deployment.

Statewide efforts are beginning to address this. The New York State Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) has released a Battery Energy Storage System Guidebook to support local governments managing BESS development.

The guidebook includes a model law outlining recommended regulations and procedures for battery systems of all sizes. Additionally, a model permit sets minimum electrical and structural review requirements for small commercial batteries. Lastly, it provides guidance on field inspections, fire prevention, and battery-specific fire code requirements.

Some groups have also proposed shifting large BESS permitting to the Office of Renewable Energy Siting (ORES). ORES is New York State’s centralized authority for permitting large renewable and transmission projects through a standardized, state-level process.

At present, ORES can only permit batteries co-located with large renewable generation projects. Large standalone BESS still require state approval in addition to local permits, rather than replacing the local process.

Advocacy groups argue that bringing standalone BESS under ORES would centralize technical expertise, override inconsistent local permitting and moratoria, and safely accelerate the storage deployment needed to meet New York’s climate and equity goals.

Ultimately, how New York aligns permitting across localities will play a central role in determining whether grid-scale battery storage can deploy at the pace and scale targeted by the state.