New York's 2050 electricity demand forecast: three drivers reshaping the grid

New York's 2050 electricity demand forecast: three drivers reshaping the grid

NYISO projects annual energy demand rising 55.8%, from 152 to 238 TWh, over the next 25 years. But, in many ways, the growth rate is less important than the shape it takes.

Three drivers are responsible, each reshaping the grid in different ways:

- Building electrification increases winter stress in what has historically been a summer-peaking system, with the heaviest additions concentrated downstate.

- Electric vehicles (EVs) concentrate charging between 10 p.m. and 3 a.m., creating the sharpest intraday load swing of any driver and extending the hours of system stress into the overnight window.

- Large loads have flat demand profiles, primarily contributing to baseload in the upstate zones.

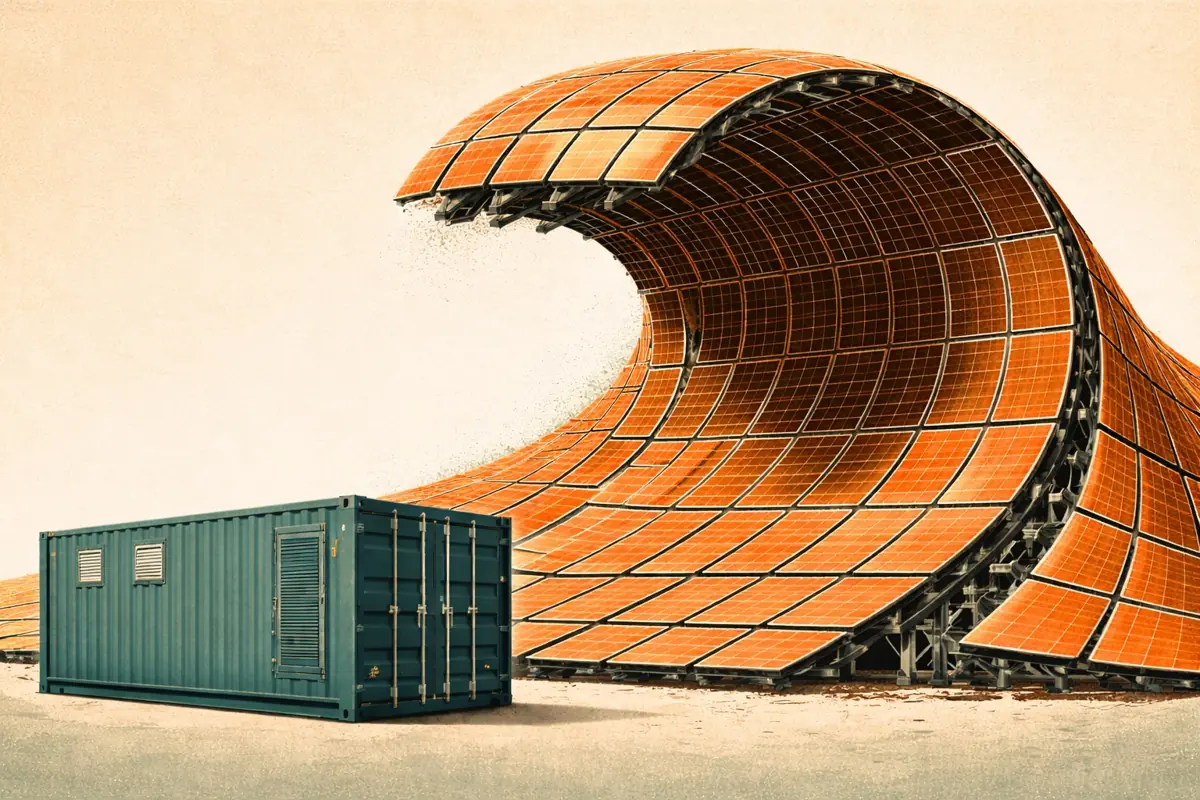

For battery energy storage, these shifts compound. Modo Energy's demand forecast model projects that they will expand BESS earning windows on multiple fronts: a second peak season in winter, steeper intraday ramps, and longer sustained discharge periods overnight.

Part 1: NYISO's forecast scenarios are split by a series of assumptions

NYISO calculates a baseline scenario and two sensitivities with higher and lower demand.

The scenarios share similar assumptions for weather trends, energy efficiency, behind-the-meter (BTM) solar, and BTM storage. They diverge on economic growth, electrification pace, EV adoption, and large load assumptions.

The table below summarizes the key assumptions that differ across NYISO's scenarios.

These assumptions produce a wide range of outcomes. Total energy demand in 2050 ranges from 200 TWh to 338 TWh, with the baseline at 238 TWh.

Modo Energy's hourly forecast profiles referenced in this article are built on NYISO's baseline inputs.

Part 2: Three major transformations define the next 25 years of electricity demand

Transformation 1: By 2050, New York needs as much new electricity as Arizona's annual consumption in 2023

The baseline forecast adds 85 TWh between 2025 and 2050, equivalent to Arizona's entire annual electricity use in 2023.

Through 2030, the system-wide demand growth of 10.8 TWh is entirely attributable to large loads, like data centers. The rest of the system actually contracts by 580 GWh. Energy efficiency and behind-the-meter solar offsets outpace early-stage electrification.

After 2030, electrification becomes the dominant growth driver.

By 2050 EVs and building electrification together add 92 TWh annually while energy efficiency saves only 30 TWh, a 3:1 ratio.

And this is the baseline, which does not assume New York meets its electrification targets. The Higher Demand Scenario, which broadly reflects those targets, shows an even larger growth in demand.

Transformation 2: Winter peaks overtake summer around 2039, creating a second BESS earning season

By 2050, baseline winter peak demand reaches 48 GW, 26% above summer.

Building electrification drives the divergence. Heat pumps add 19 GW to winter peak but only 2 GW to summer, nearly a 10:1 ratio. EVs reinforce this modestly: winter EV peak demand runs 1.4x summer by 2050, adding 2.7 GW to the seasonal gap.

Summer peak grows at 0.8% CAGR. Winter peak grows more than three times faster at 2.8% CAGR, overtaking summer around 2039 in the base case. The Higher Demand Scenario brings the crossover forward to around 2035. Even in the Lower Demand Scenario, winter overtakes summer by the mid-2040s.

Regardless of the scenario, BESS owners gain a second, eventually larger, earning window without the summer opportunity shrinking.

Electrification also widens the range of possible winter peak outcomes.

In 2025, NYISO's weather scenarios show winter peak varying by 13.6% from mild to near-worst-case conditions, less dispersed than summer's 18.6%. By 2050, winter's spread reaches 20.3% while summer stays flat.

For batteries, this is a pricing signal. The more weather-sensitive the winter peak, the steeper the price spikes during cold events, and the more a fast-dispatching asset captures in the hours that matter most.

Transformation 3: A 9-hour discharge window replaces the afternoon peak

In 2026, New York's summer load peaks in the late afternoon and its winter load follows a conventional dual-hump pattern. By 2050, both seasons look fundamentally different.

In summer 2050, the midday trough stays low as BTM solar capacity grows to 15 GW, suppressing mid-morning and early-afternoon demand. The evening ramp steepens as EV charging and residual cooling load stack onto the late afternoon. Modo Energy's hourly profiles show the summer ramp growing from 5.6 GW in 2026 to 7.9 GW by 2050.

The winter transformation is more dramatic. By 2050, load dips to 28.2 GW by early afternoon before ramping 8.9 GW to a first peak of 37.1 GW at 6 p.m. It dips briefly, then climbs again past 10 p.m. as overnight EV charging stacks onto heating load. The system peaks at midnight, reaching 39 GW.

The result is a broad plateau above 37 GW from 6 p.m. to 3 a.m. This shifts the hours of highest system stress from a summer late-afternoon window to a 9-hour winter overnight window, a fundamentally different discharge opportunity for storage.

Part 3: Three drivers reshape the grid at different speeds, in different places, with different levels of certainty

Driver 1: Building electrification adds load downstate, but its pace hinges on a suspended state law

Energy consumption from building electrification rises from 411 GWh in 2025 to 42,855 GWh in 2050, a 104-fold increase.

The impact concentrates downstate. New York City and Long Island account for 51% of total building electrification energy by 2050. These are also the most transmission-constrained parts of the grid.

The rate of building electrification is the forecast's most uncertain variable, as it is closely linked to policy outcomes.

Most recently, the All-Electric Buildings Act was suspended in November 2025 pending a Second Circuit appeal. This weighs on the outlook for baseline electrification assumptions. Even in the Lower Demand Scenario, however, building electrification adds 16.3 GW of winter peak - just at a slightly slower pace.

The question is not whether electrification happens but how fast.

Driver 2: A 25-fold EV fleet expansion is the most certain driver, consumer-led and consistent across all scenarios

New York's EV fleet grows 25-fold to 9.3 million by 2050.

Energy consumption rises from 1,353 GWh to 49,535 GWh, with growth steepest through the late 2030s before the fleet approaches saturation.

The primary impact is on the overnight load shape. EV charging concentrates between 10 p.m. and 3 a.m., peaking at 1 a.m. On an average day in 2050, EV load ranges from a 345 MW morning low to a 901 MW overnight peak, although during the single most-stressed hour of winter, EVs can add as much as 9.3 GW to coincident peak demand.

EV adoption is also consumer-driven and less exposed to political risk than building electrification. The growth trajectory is more consistent across NYISO's three scenarios.

Driver 3: Large loads arrive first and plateau by the mid-2030s, but the forecast is only a fraction of the 6 GW interconnection queue

Large load demand rises from 3.7 TWh in 2025 to 15.1 TWh by 2030 and plateaus at 19.3 TWh by the mid-2030s. The facilities are overwhelmingly data centers and semiconductor fabs with near-flat demand profiles across hours and seasons. Peak impacts are nearly identical in summer and winter: 2.6 GW by the late 2030s, holding through 2050.

Growth concentrates upstate. Central leads, followed by North and West. Downstate zones (Millwood, Dunwoodie, and New York City) contribute nothing.

The forecast plateaus because NYISO includes only the large load projects, queued and pre-queue, it considers likely to connect.

The interconnection queue itself is much larger: 6,055 MW across 29 proposals.

Data centers account for 72% of nameplate load, concentrated in Mohawk Valley, West, and Central. Semiconductor manufacturing adds another 22%.

Downstate grid constraints block delivery where upstate transmission headroom allows it. Millwood has 200 MW in the queue but zero large load energy in the forecast.

Large loads do the least to create direct battery value. Flat 24/7 consumption tightens the system without producing peaks. The BESS case from data centers is indirect: they raise the baseline level of demand, so that when peaks do arrive, the system is closer to its limits — making scarcity and congestion more likely.

Part 4: These shifts favor fast-dispatching storage

The BESS opportunity in NYISO is defined by the changing shape of demand, not just the total. Building electrification creates a second stress season. EVs extend that stress into a 9-hour overnight discharge window. Large loads absorb supply headroom that makes peaks more valuable.

Geography amplifies the opportunity. Electrification concentrates downstate, where transmission constraints already drive the highest capacity prices. Large loads concentrate upstate, raising baseload demand across the system while leaving the downstate premium intact.

Across all three NYISO scenarios the directional story is the same: a shift from summer-peaking to winter-peaking, steeper ramps, longer evening stress windows, and greater weather sensitivity. Every one of those shifts favors fast-dispatching storage.

All of the above shifts are incorporated into Modo Energy's NYISO BESS revenue forecast, where they flow through the production cost model into the price signals, dispatch windows, and project-level returns that define the battery storage investment case.