WEM: An introduction to Australia’s Wholesale Electricity Market

WEM: An introduction to Australia’s Wholesale Electricity Market

The Wholesale Electricity Market (WEM) is Western Australia’s largest electricity market, covering the entire South West Interconnected System. It spans over 260,000 square kilometres and supplies more than 1.2 million households and businesses.

The WEM operates as a competitive energy and capacity market designed to ensure reliable supply in a long, islanded grid with no interstate interconnections. This makes its market design, pricing mechanisms, and capacity framework central to maintaining system security.

In this article, we outline how the WEM is structured, how capacity is valued and allocated, and what these mechanisms mean for assets participating in the system today.

Executive summary:

- The WEM is a single-region market with one wholesale price. It covers most of Western Australia's electricity demand.

- Thermal generation makes up 60% of the generation stack.

- Battery energy storage capacity has doubled in the last 12 months, reaching 1.4 GW in December 2025.

- Generators earn revenue from both the energy and capacity markets.

The WEM is the largest energy market in Western Australia

The WEM operates as a single-region market with one wholesale price, centred on the Perth load area. It extends north to Kalbarri, south to Albany, and east to Kalgoorlie, covering the majority of Western Australia’s population and electricity demand.

The WEM grid, commonly known as the South West Interconnected System (SWIS), spans more than 8,000 km of transmission lines and 90,000 km of distribution lines, connecting around 1.2 million households and businesses. This network supports a diverse generation mix and underpins the WEM’s dispatch, settlement, and reliability framework.

The WEM is considerably smaller than the NEM, with a maximum operational demand of about 4.4 GW. It shows both summer and winter peaks. Summer peaks are higher because air-conditioning load drives sharp late-afternoon demand. Winter peak demand is lower but persists for longer, driven by heating and extended evening demand.

The system also hosts large industrial loads linked to mining, mineral processing, gas production and export. Major users include alumina refineries, mineral processing plants, and other energy-intensive facilities. Industrial consumption makes up roughly 40–45% of annual operational demand in the SWIS.

Thermal generation supplies most of this demand, but in recent years the mix has shifted toward renewable generation.

Thermal generation services around 60% of demand in the WEM

The generation fleet includes 1.2 GW of black coal capacity and 3.4 GW of gas-fired power stations, which together form the bulk of the system’s dispatchable supply. Rooftop solar is the largest source of renewable capacity at around 3 GW, which can meet up to 80% of underlying demand in favourable conditions.

Utility-scale solar remains limited, with wind supplying most of the grid-scale renewable output. The system now includes several large battery energy storage assets (>100 MW), all with four-hour duration, except for the initial pilot installation.

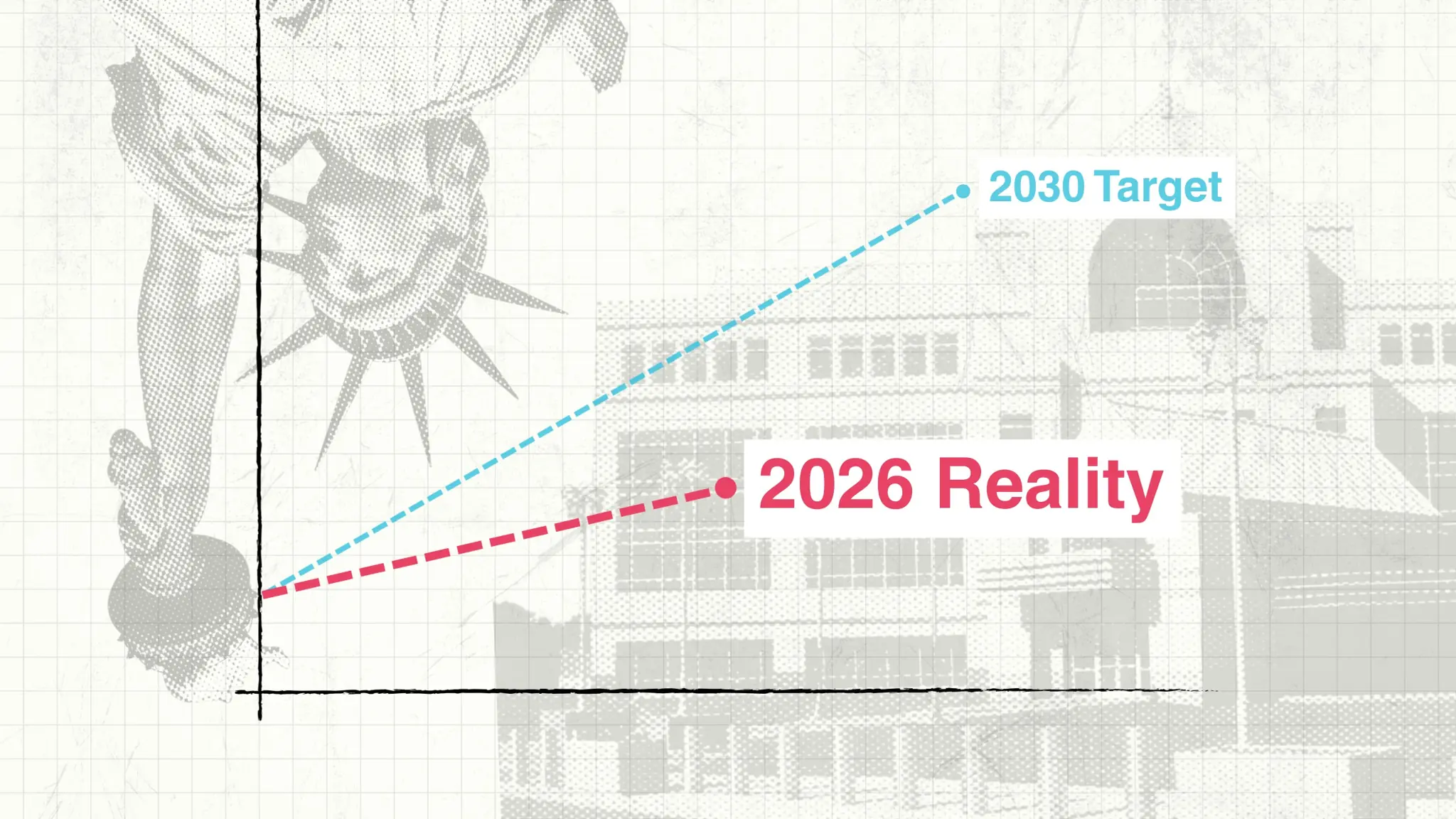

Nearly 1.7 GW of thermal generation is expected to retire from the SWIS over the next decade, including the entire coal fleet. AEMO’s 2025 WEM ESOO schedules the closure of all remaining coal units by the end of 2029 to meet the state's 2030 target for withdrawing all government-owned coal plants.

Large-scale storage will play a central role in managing the coal exit and maintaining system security.

The market: Generators earn revenue from both a real-time and a capacity market

The WEM operates with two core market mechanisms: a real-time energy market (the balancing market) and an annual capacity market (the Reserve Capacity Mechanism). The balancing market manages dispatch and price formation every five minutes. This ensures supply and demand remain aligned in real time. The capacity market secures sufficient capacity to meet forecast peak demand. Together, these mechanisms coordinate short-term system operation and longer-term reliability.

This framework flows into the balancing market, which manages real-time dispatch and price formation.

The balancing market aligns supply and demand in real time at five-minute granularity

AEMO operates the market using the WEM-Dispatch Engine (WEM-DE) to settle supply and demand at a 5-minute granularity. This is known as the balancing market. WEM-DE has a similar dispatch methodology to the NEM version (NEM-DE), co-optimising across the balancing market and the Frequency Co-optimised Essential System Services (FCESS), while accounting for bids, transmission constraints, and grid security.

As of December 2025, the balancing market price floor sits at –$1,000/MWh, with a price cap of $1,000/MWh. However, AEMO dynamically adjusts the cap ±$100/MWh depending on market conditions.

The combination of a low price cap and modest demand means that the entry of large batteries has had a significant dampening effect on volatility. Kwinana was the first battery to come online in May 2023 and started this compression. Still, rapid rooftop solar growth and multiple coal outages offset its effect, driving high volatility through 2024.

The commissioning of Kwinana 2 (225 MW / 900 MWh) and Collie 1 (219 MW / 877 MWh) in late 2024 significantly compressed spreads, limiting arbitrage opportunities from the balancing market.

Frequency control is managed through the FCESS market

AEMO operates five Frequency Co-optimised Essential System Services (FCESS), designed to keep the system frequency at 50 Hz:

- Regulation Raise (>49.95 Hz)

- Regulation Lower (<50.05 Hz)

- Contingency Reserve Raise (<49.95 Hz)

- Contingency Reserve Lower (>50.05 Hz)

- Rate of Change of Frequency (RoCoF) Control Service

The Contingency Reserve market has three time frames: Fast Contingency Reserve (6 seconds), Slow Contingency Reserve (60 seconds), and Delayed Contingency Reserve (5 minutes).

There is also a System Restart Service, which AEMO contracts for under the ESM Rules framework.

The Reserve Capacity Mechanism provides generators credits for providing peak and flexible services

A low price cap limits energy price volatility, so generators need another revenue stream to make their return. This comes in the form of a capacity market. AEMO runs the capacity cycle from October to September and procures capacity two years in advance.

Assets receive monthly payments for providing their capacity. These payments are determined by several factors, the first being the Benchmark Reserve Capacity Price.

A 200 MW / 1200 MWh battery determines the Benchmark Reserve Capacity Price (BRCP)

AEMO and the Economic Regulation Authority define the BRCP as the annualised capital cost per megawatt of a reference technology. This also includes fixed O&M, fuel costs, insurance, and cost escalators. Previously, AEMO used a 160 MW OCGT operating in the WEM as the reference technology, but in September 2025, it switched to a 200 MW / 1,200 MWh lithium-ion battery, up from the earlier 200 MW / 800 MWh specification.

The market sets the Reserve Capacity Price (RCP) as a multiplier between 0.5 and 1.5 of the BRCP, and this price determines capacity payments.

In each capacity cycle, AEMO specifies the required capacity across both peaking and flexible (long-duration) services. It then assigns capacity credits to facilities based on several criteria (discussed later). The ratio of assigned credits to the target forms the BRCP multiplier. There are separate multipliers for peaking and flexible criteria. When assigned capacity exceeds the target, the RCP falls below the BRCP, as seen from 2005–2024. The reverse occurs when the market is undersupplied.

Assets receive Flexible Capacity Credits (FCC) based on their ability to defend a six-hour window

AEMO defines a 6-hour evening block, the Electric Storage Resources Obligation Interval, which sets the criteria for FCC. Assets capable of covering the full interval receive the maximum FCC for their accredited capacity.

Batteries with shorter duration cannot defend the entire window and therefore do not receive the full credit allocation. Efficiency losses and degradation may further reduce FCC.

This framework incentivises batteries in the WEM to be built with at least 6 hours of duration to maximise their capacity-market value.

Assets are assigned Peak Capacity Credits based on their contribution to reducing Loss of Load risk

Peak Capacity Credits (PCC) are allocated according to an asset’s expected availability during periods with elevated Loss of Load Probability (LOLP). AEMO runs probabilistic modelling to identify intervals where the system is most at risk of unserved energy and then assesses the contribution each facility can make to reducing that risk.

This assessment considers forced-outage rates, expected dispatch capability, network constraints, and technology-specific performance assumptions. The resulting contribution defines the number of PCCs assigned to the asset.

The grid: The structure of the SWIS and its major subregions

Although relatively small, the SWIS is divided into 11 primary generation and load subregions, each with its own generation mix and transmission characteristics.

A high-level summary of the major regions:

- North (North Country, Mid West): High renewable penetration but heavily constrained by the network, with several large mining loads across the region.

- South West (Collie, Bunbury, Muja): The system-strength anchor of the grid, historically dominated by coal and now transitioning toward large-scale batteries and firming, alongside major alumina processing.

- Metro / Kwinana (Perth Metro, Kwinana Industrial Area): The demand centre with strong network infrastructure and the highest concentration of gas generation and battery storage.

- South East (Great Southern, eastern Goldfields fringe): Limited hosting capacity with long transmission lines and significant industrial demand from agricultural processing.

Transmission Loss Factors and Network Access Quantities shape asset economics

Transmission Loss Factors (TLFs) combine an asset’s Marginal and Distribution Loss Factors and quantify losses on the marginal unit of energy as it moves from the generator to the point of consumption. These are then applied directly to the asset’s revenues.

Network Access Quantities (NAQs) are the maximum export limits that a generator can send into the grid. An asset cannot be dispatched or accredited above its NAQ. Network studies set NAQs by determining how much export the system can safely accommodate, and they also reflect Western Australia’s historical curtailment-protection framework, where older “foundation” generators retain priority access and new entrants take the remaining headroom.

The WEM’s transition hinges on flexibility, reliability, and network access

The WEM is entering a period of rapid structural change. Coal retirements, rising renewable penetration, and the increasing role of batteries are reshaping both operational dynamics and revenue pathways. The balancing market, FCESS, and the capacity market each play a distinct role in coordinating reliability and system security.

As the system transitions toward a renewable-dominated supply mix, storage becomes central to maintaining adequacy, frequency stability, and flexibility. Understanding how the WEM’s market design interacts with technology capabilities will be critical for investors, developers, and policymakers as the SWIS moves through its next phase of development.