15 November 2023

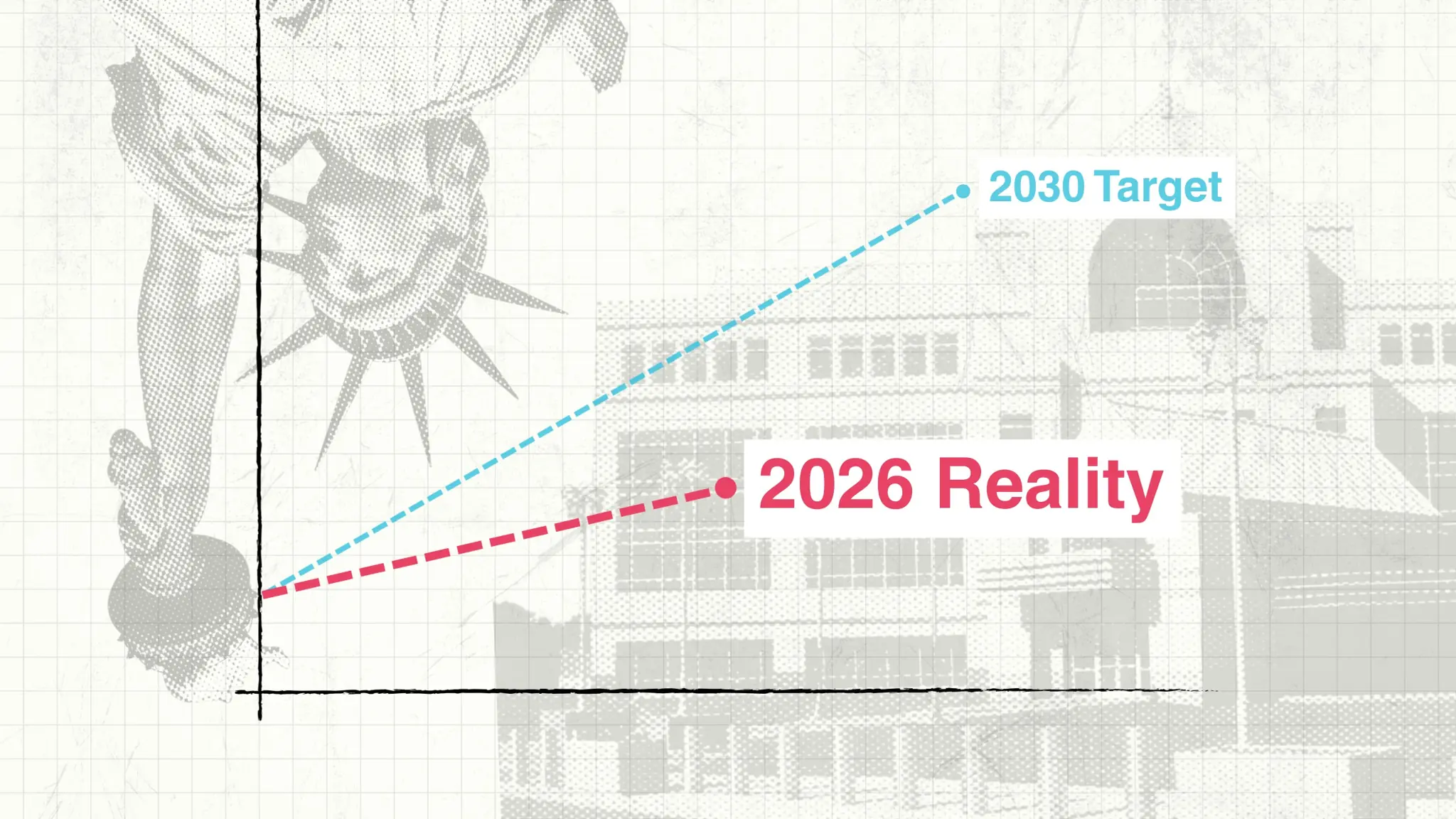

Early bidding strategies in the Enduring Auction Capability: The impact on revenues

Written by:

Early bidding strategies in the Enduring Auction Capability: The impact on revenues

The Enduring Auction Capability (EAC) has been used for procuring response services for delivery since Friday November 3rd 2023. Now that the first set of results is available, we can see if any bidding patterns have emerged in these early stages.

Get full access to Modo Energy Research

Already a subscriber?

Log in