Battery energy storage acquisitions: how has the landscape changed?

Battery energy storage acquisitions: how has the landscape changed?

Download the data behind this Deep Dive here! Something missing? Just drop me an email with the details - shaniyaa@modo.energy - and I’ll update the spreadsheet.

Battery energy storage systems - like any other privately-owned asset or commodity - get bought and sold. Since 2017, at least 2.7 GW of battery projects have changed hands in Great Britain - according to company reports, news stories, and press releases.

But how has the landscape for battery acquisitions changed in recent years? Who has been buying and selling these assets? And what is the actual cost of a battery?

Batteries are bought and sold at different stages of the development cycle

Battery acquisitions are pretty common. Over the past few years, lots of battery energy storage projects in Great Britain have changed hands - and these acquisitions can take place at any stage of the battery’s development process.

So, what do these different stages actually look like?

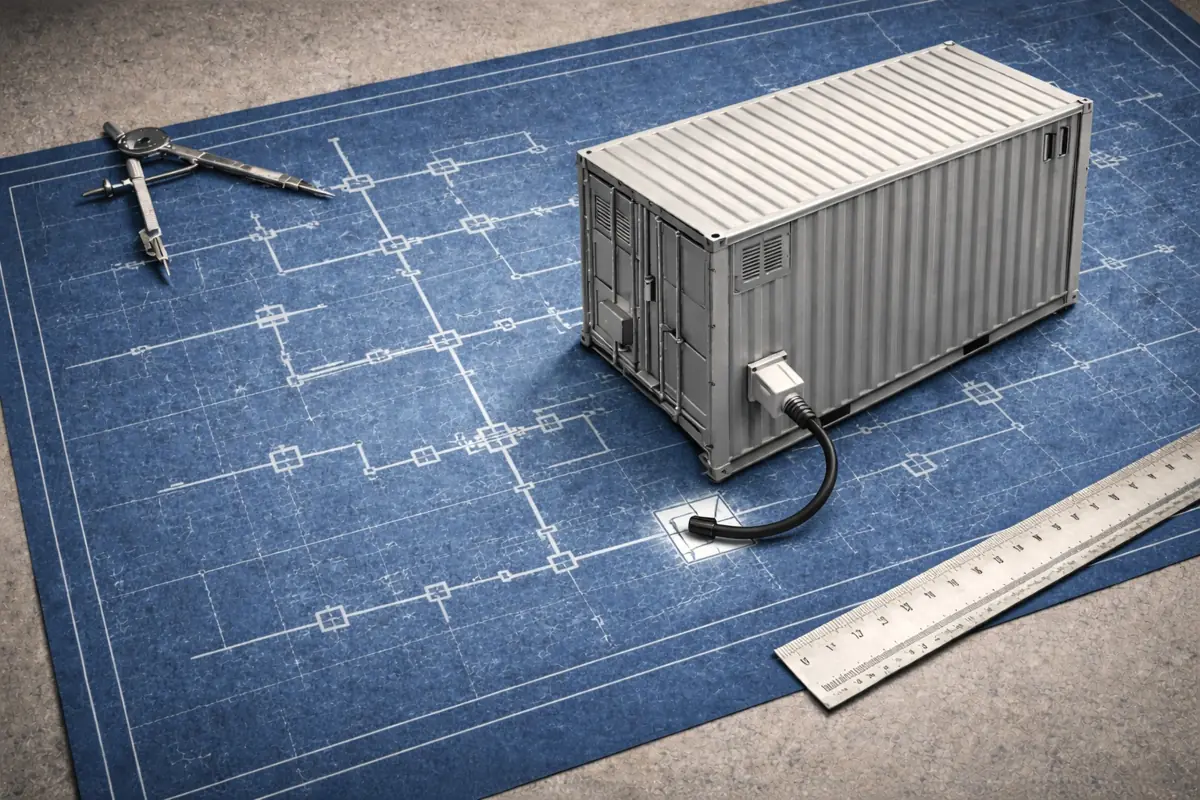

Shovel-ready

“Shovel-ready” sites are sold before construction has even begun. Generally, at this stage, the buyer is acquiring a plot of land - with the appropriate planning permission and grid connection agreement.

Of the 2.7 GW of battery acquisitions that we’ve tracked, 2.1 GW of that volume has been in shovel-ready sites.

Pre-operational

These assets can be split into two groups: those sold during the construction phase, and those sold after the battery has been built. In both cases, the project is sold before the battery has become “operational” - it physically exists (to some extent), but it hasn’t actually bought or sold any electricity yet.

Pre-operational sites make up around 330 MW of battery acquisitions.

Operational

And, lastly, there are acquisitions for “operational” batteries. Essentially, the battery changes hands after it is up and running (i.e. it has entered markets, and is making money).

Operational sites make up around 200 MW of battery acquisitions.

The acquisition of “shovel-ready” projects is the new normal

Before July 2021, most acquisitions were for batteries that were already operational at the point of sale. However, since then, it’s been far more common to see shovel-ready and other pre-operational sites change hands.

So, what’s behind this shift?

Early movers in the battery space were still finding their feet in an emerging market

The battery energy storage market is newer - or less “mature” - than some of the markets for other renewable technologies. This explains the change in battery acquisition patterns. As the market has evolved, so have the organizations within it.

Early on, some companies developed, owned and optimized their own sites - but later pivoted to specialize in one particular area. Others have exited the sector entirely. Therefore, some organizations that used to own batteries have ended up selling some of their sites - or even whole portfolios.

Some organizations are more willing than others to take risks in an evolving market...

A number of the operational sites that changed hands pre-July 2021 had contracts to provide Enhanced Frequency Response (EFR) - a grid support service, run by National Grid ESO, which has since effectively been replaced by other frequency response services (e.g. Dynamic Containment).

The first EFR contracts were awarded in 2016, and lasted for four years. However, new EFR auctions were never launched - and frequency response services now have much shorter-term contracts.

Short-term contracts bring an element of risk (you can never be sure what the price will be from one auction to the next) - and this may not have suited some asset owners (who preferred the security of longer-duration, fixed contracts).

Other organizations were willing to take on this market risk - and built their business cases around doing so. These companies sought to establish themselves as specialist battery energy storage owners - and have acquired projects in order to achieve this.

Gresham House, Gore Street and Pulse Clean Energy have bought the most assets from third-parties - in terms of both the number of individual sites, and the total rated power (MW) of these sites.

Some companies also acquire projects from organizations operated under the same parent company. Gresham House (with acquisitions from Gresham House DevCo), Harmony Energy Income Trust (acquiring from Harmony Energy Limited), and TRIG (acquiring from RES) are the main examples of this - these projects are excluded from the charts above.

The acquisition of battery energy storage comes in many forms

Battery projects can also be acquired as part of other renewable developments. Cleve Hill (Project Fortress) was acquired by Quinbrook in 2021, Durham was acquired by Gresham House in 2022, and Octopus Renewables acquired Cambridgeshire in June 2022. These are all examples of battery energy storage projects included in the acquisition of solar farms.

It’s not just battery projects that have changed hands - a more extreme example is the acquisition of an entire company. In 2019, EDF acquired the specialist battery energy storage developer Pivot Power, bringing it into their renewables division. This provided EDF with battery projects in development (and the skills to construct and operate these) - and it gave Pivot Power the ability to fund and construct these projects.

What determines the price of a battery project?

The “cost” of battery energy storage sites isn’t always easy to figure out - and the reported price paid (where there is any reporting) often doesn’t adequately represent the actual cost of the battery.

Ultimately, these deals take place in private - and usually with millions of pounds at stake. It is often not in the interests of the buying and/or selling parties for the details of those deals to be made public.

We have combed through news articles, press releases, and company reports - and spoken to people within the industry. This gives us an idea of price - but these numbers should be taken as a general guide, not as gospel. As we don’t know the actual figures involved in many cases, we are dealing with a pretty small sample size.

However, in general, organizations are spending more on batteries than before - but they’re also getting more bang for their buck!

- Batteries are getting bigger (higher rated power, higher energy capacity). It used to be common to see batteries in the 8-10 MW range come online - we’re now entering a world where 100+ MW sites will be the new normal.

- As a result, projects cost more. For example, Richborough Energy Park - a 99 MW site - was sold earlier this year, and is reported to have cost £74 million.

Duration has the biggest impact on the cost of a battery project

The buying and selling of longer-duration (> one hour) projects has become more common over time.

The average cost of all battery acquisitions over the past four years - as they’ve been reported - is £570,000/MW.

However, some of these sites have changed hands between two arms of the same company. For example, Wickham Market and Thurcroft were sold in 2020 - from Gresham House and Noriker, to Gresham House Energy Storage Fund. Therefore, the reported prices might not reflect the true market value of these assets (had they changed hands between entirely unrelated organizations).

Additional duration requires additional energy capacity - which means more cells. As such, longer-duration battery projects tend to be bought and sold for more money than shorter-duration projects.

What other factors determine the price paid for a battery project?

Age

Batteries degrade with use, which means they have less available energy capacity. In general, the older an asset, the more it will have degraded (although other factors, such as how the battery has been operated, will also impact degradation).

Therefore, you would expect older assets - which have degraded more - will be cheaper than newer assets. All of the one-hour systems we’ve tracked here were already operational at the point of sale - and so may have been acquired at a discounted price, compared with a brand-new system.

Size

In general, bigger batteries should cost less per MW than smaller systems - because of economies of scale. This might explain why Bacup - an 8 MW battery, acquired by Tion - cost more than might normally be expected for a system of its duration.

Pre-existing contracts

Some batteries have been sold while holding high-value, long-term contracts. In the past, these have included Enhanced Frequency Response - and, more significantly, Capacity Market contracts without de-rating factors.

When Glassenbury and Cleator were sold in 2019, they both had EFR and Capacity Market contracts. The long-term value of these capacity market contracts likely resulted in a premium being paid for the two systems, because of the high future revenues the contracts would provide.

These high de-rating factor Capacity Market contracts are no longer available, and so its unlikely that any newer sites will see such a premium on their acquisition cost.

Location

A battery project may be located somewhere particularly advantageous for the buyer. It may be well-placed to manage a particular constraint (and make money in doing so), or it could be located near to other projects in the buyer’s portfolio.

- The areas in which the most battery project acquisitions have taken place are the Northern, North Western and South of Scotland regions.

- However, in terms of total capacity (MW) bought and sold, the South Eastern region is top - 640 MW.

- This is a result of the acquisitions of large-scale projects - such as Richborough Park (99 MW), Sheaf Green Energy Park (249 MW), and Cleve Hill (150 MW). These projects are well-positioned to support constraints in this area.

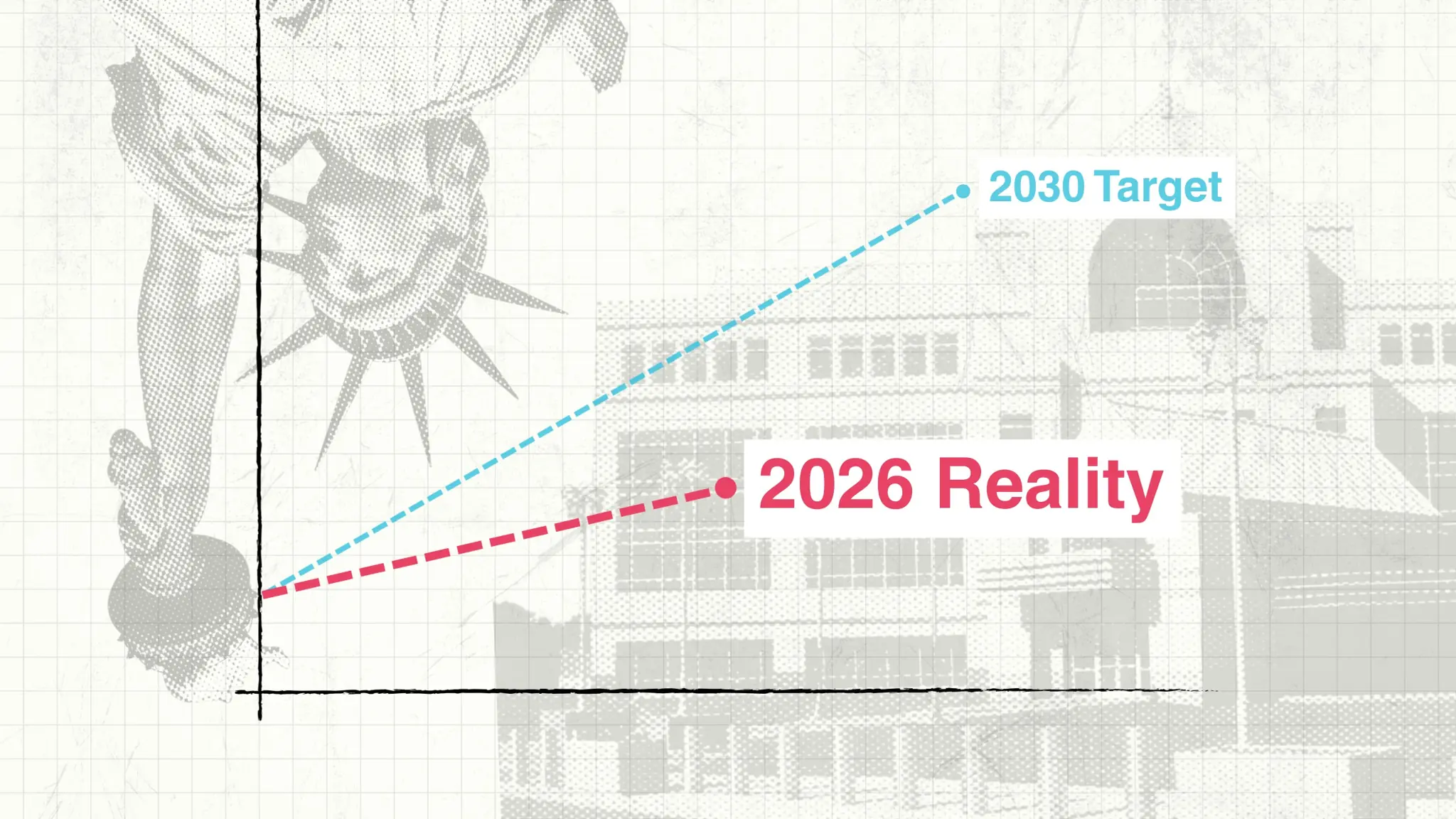

The future of battery acquisitions

As the market has matured, there’s been more buying and selling of “shovel-ready” projects. However, this shift may not be permanent. As the market continues to evolve, some larger organizations may be interested in building portfolios from existing sites.

Alternatively, we may see developers who specialize in acquiring land, planning permission, and grid connection agreements - before selling on the site to another organization - continue to thrive.

Download the data

You can now download the data behind this Deep Dive - just head here!

We want to make sure that this database gives the fullest possible picture of battery acquisitions - so, if you think something’s missing (a whole site, or even just a couple of details) or needs updating, please get in touch: shaniyaa@modo.energy

Updates to the database will not necessarily result in updates to the graphs or numbers in the article. However, we may use the updated database in future Phase articles.