Following the end of solar energy subsidies, build-out has slowed massively. But, last year, there was a bounceback (of sorts). In response to rising energy prices, Great Britain saw a 13% increase in rooftop solar capacity in 2022.

More solar capacity tends to mean lower power prices - so, what are the impacts of this increase? And when can we expect to see more zero or negative daytime power prices?

The increase in solar capacity

2022 saw the biggest annual increase in Great Britain's solar capacity since the Renewable Obligation scheme was closed to new solar projects in 2017. 650 MW of new capacity was added - with rooftop solar making up the bulk of this.

The 13% increase in rooftop solar capacity is the biggest increase since changes made to the Feed-in Tariff scheme in 2015 (this subsequently closed entirely in 2019). This is due to the increase in energy prices for consumers since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Rooftop solar buildout has been quicker than grid-scale projects because their size means they are: quicker to build, face fewer planning restrictions, and have easier access to grid connections.

Has solar generation increased as a result?

Despite this increase in capacity, we have yet to see the same increase in generation. Solar generation in the first four months of 2023 fell short of the levels seen during the same period last year.

However, summer is coming. It looks as though we’ll see record levels of solar generation in month of May.

How does solar generation impact power prices in Great Britain?

Almost all solar capacity is embedded generation - i.e. National Grid ESO has no way to re-dispatch it, like it can with (most) wind generation through the Balancing Mechanism.

Solar is either generating, or it isn’t - it can’t be turned on and off. When there’s lots of solar power being generated, demand (and prices) are lower - and when there’s less, demand (and prices) are higher. (In theory, anyway.)

The control room then works around these demand fluctuations by turning other technologies up or down, depending on need.

How is solar generation changing Great Britain’s demand shape?

Several factors influence Great Britain’s daily demand curve. These include time of day, temperature, and day of the week.

The level of embedded generation - and particularly solar - is becoming one of the most significant.

Minimum national demand has reduced across the day since 2013 - but by far the biggest reductions can be found during peak solar hours (between 9am and 5pm).

2020 saw daily average demand hit all-time lows. Post-lockdown, demand has risen again - but the midday dip remains.

So, what impact is solar having on power prices?

Currently, solar generation is having an impact (albeit relatively limited) on prices.

However, there’s not enough solar capacity to regularly push CCGTs out of the generation stack (see our Energy Academy episode to see how this works). Therefore, CCGTs still dictate the price the vast majority of the time.

That said, prices have occasionally fallen to near (and even below) zero during peak solar hours.

What are the conditions needed to drive prices down?

Most solar generation has no way to have its output curtailed - even if prices fall to zero. This means solar will continue exporting to the grid, regardless of price. On the sunniest days, this can lead to zero or negative prices.

Case study: 11th June 2022

High solar generation in the middle of the day, combined with embedded wind, helped reduce national demand to around 16 GW at 3pm. This, in turn, impacted the wholesale market - with the low demand pushing prices to zero (and below) for three hours.

Currently, standalone solar generation is insufficient to tip the scale on its own. We only see prices fall during the middle of the day when high solar output coincides with higher wind and low national demand.

But 2020, with its drop-off in national demand, offered us a glimpse of what the future might look like for daytime power prices.

What can 2020 tell us about the future of negative prices?

During the lockdowns in 2020, many commercial and industrial operations stopped - but renewable electricity output did not.

Because of this, demand hit record lows from April to June. This led to negative daytime prices for the first time ever - and far more of them than we’ve seen since.

As national demand fell below 25 GW, we saw more and more occasions where prices hit zero, or even turned negative. On each of these occasions, embedded solar generation was a big contributor to falling national demand.

As national demand falls, the likelihood of zero or negative pricing increases. There is a drastic step-increase in the likelihood of zero or negative pricing when national demand falls below 18 GW.

Given that demand across the period was 3.5 GW lower than today, how do we extrapolate this to ‘normal’ demand levels?

How much more solar generation is needed for us to hit 2020 levels?

In 2020, there was a 37% chance of zero or negative prices when national demand fell below 18 GW. So, what’s actually needed for national demand to hit this level regularly?

For national demand to drop this low during daytime hours, an average 14.9 GW of embedded solar and wind generation is needed. On days with the lowest demand levels, this number falls - the lowest needed to hit 18 GW overall demand in 2022 was just 7.9 GW during peak solar hours.

If we assume an average wind load factor of 30%, this means embedded wind generation makes up roughly 1.5 GW (meaning national demand levels of 16.4 GW). To hit the 18 GW overall demand, solar would need to generate an average 9.4 GW during midday hours.

So, when is this likely to happen?

When might we hit this level?

Based on this historical behavior, we’ve projected the frequency of daytime negative pricing over the next five years (2023-2027).

We expect to see instances of zero or negative daytime pricing start to pick up in 2025 - when Britain is projected to have 18.7 GW of solar capacity installed. By 2027, this number could reach 23.2 GW.

The frequency of these events will increase year-on-year. But what does this mean for future solar projects - and for battery energy storage systems?

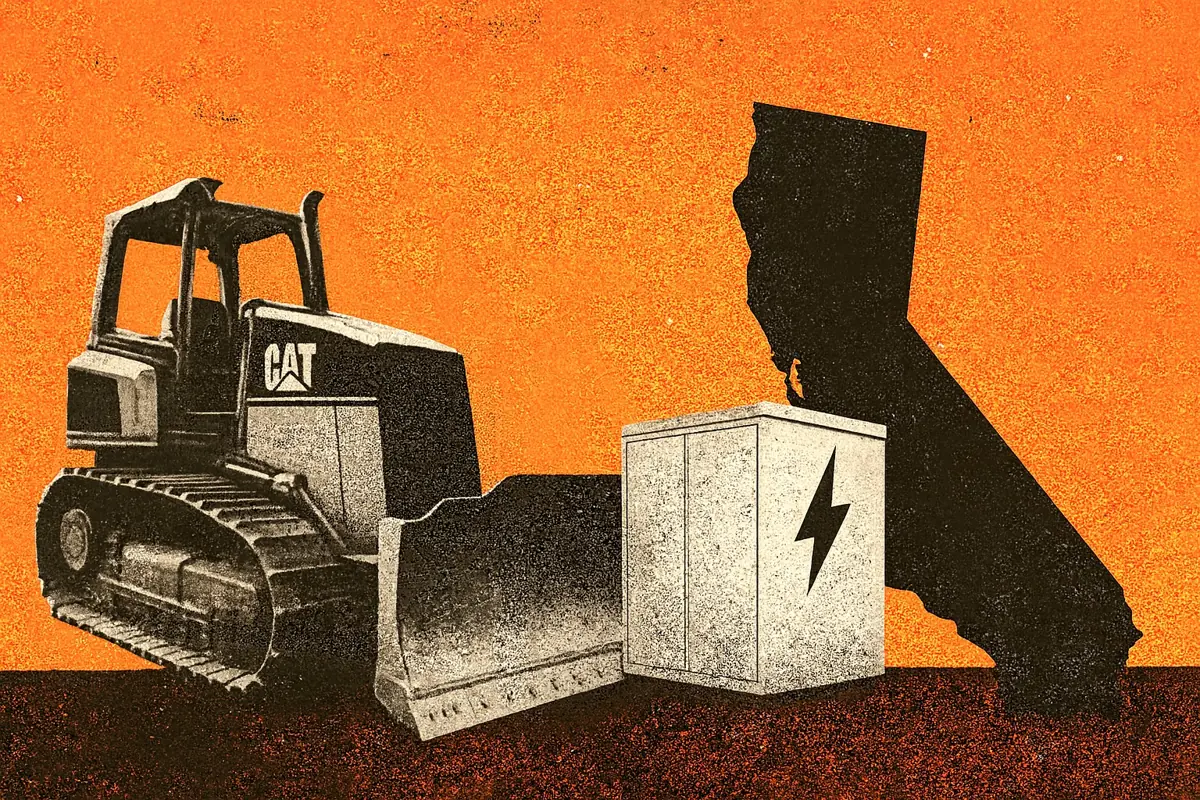

Price cannibalization

To date, solar in Great Britain has been pretty safe from price cannibalization - where additional solar generation reduces the price it can sell for significantly.

However, with the growth in solar generation capacity, we expect a decline in average power prices throughout the day. In the next five years, there is an increased likelihood that power prices will drop to zero (or below) when solar is at its highest.

We can see from other markets - such as Australia and California - that this can quickly erode the average price solar receives for its power, also known as its capture price.

What does this mean for battery energy storage?

However, an increase in solar price cannibalization is a good thing for battery energy storage - provided there are also high prices at other times of the day.

It lowers the cost of charging - plus, the increase in negative prices means batteries will actually get paid to charge up. This, in turn, increases the potential arbitrage revenues for operators.

This is also a significant motivating factor in the development of co-located solar and storage projects (or portfolios). Combining storage with solar can start to offset some of the risks of cannibalization for solar owners.